The Bill of Rights was not initially considered to be important by the founders. It was only 15 years after the signing of Thomas Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, which broke America free from her English shackles in 1776, that a Bill of Rights was ratified. But let’s backtrack just a bit and ask, “where exactly does the idea of a ‘Bill of Rights come from?”

While it is true that the American colonists declared their independence from England in 1776, with them they brought the tradition of writing documents designed to protect individual liberties—a tradition that could be dated as far back as 1215 with the passage of Magna Carta.

In 1215, England’s King John was petitioned by the country’s powerful barons to agree to a laundry list of concessions, or a charter of liberties known as the Magna Carta. The charter would be seen as the first written constitution in European history.

In effect, it subjected even the monarch to a rule of laws, protecting individuals and their liberty from the crown’s abuses of power, asserting the individual’s right to petition their government and his right to a trial by a jury of his peers.

The most cited passage states that “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions…” in a vein similar to that of the United States’ Fifth Amendment.

The charter paved the way for the English Bill of Rights, coming just a year after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, which effectively established the power of parliament. The revolution moved the country away from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy. Under the new government, William III and Mary II promised to govern “according to the laws of parliament.”

Just a year later, the English adopted the “Bill of Rights,” which served as the foundation of the government since the revolution. The bill was not allegedly intended to rewrite the law but to explicitly state the law that already existed. This idea was reiterated by Thomas Jefferson in his 1825 letter to Henry Lee when he said that he did not write anything new in his Declaration of Independence, but intended only to express what was already in the “American mind.”

Along with the English’s “Bill of Rights” came the passage of the Toleration Act of 1689, which granted religious freedom to Protestants within the country, yet another influence the American colonists would use as the basis of the First Amendment.

In the heart of the American colonist existed the Englishman who agreed with previous colonial charters stating that those in the New World deserved the same rights and privileges as those in the Old. They were, after all, Englishmen. This is why James Madison, who would become the fourth president of the United States, fought to include the U.S. Bill of Rights in the Constitution. Well-read in English law and politics, Madison was all too familiar with the Magna Carta of 1215 and the English Bill of Rights, understanding the importance of protecting the citizens of this new country.

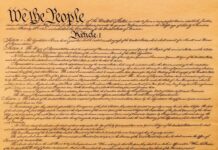

On December 15, 1791, the first Ten Amendments were ratified and included in the United States Constitution.